Product Innovations Designed to be Hacked

Contents

[hide]Case Study: Raspberry Pi

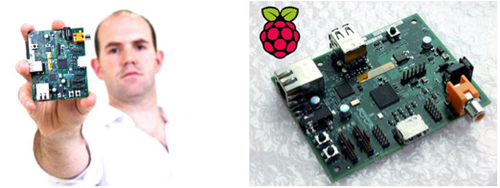

Figure 1. Raspberry Pi – the £22 computer designed to be hacked.

At the absorb and exploit end of the firm-hacker response spectrum is the non- profit UK based Raspberry Pi Foundation who introduced the Raspberry Pi computer in 2012 designed with the sole purpose of being hackable by anyone, of any age and to encourage basic computer science and programming skills in school children.

As reported in the press, the UK IT curriculum merely teaches students how to operate software packages and has been described as “demotivating and dull” by the current Education Secretary Michael Gove as [Joyce, 2012]. Students should be encouraged to learn how to modify, develop and reconfigure software for themselves as they see fit, avoiding the mysterious black box of tricks mind-set. As a consequence it is claimed that lack of coding skills is a significant barrier to future growth and holds back the UK in the digital economy age.[1]

How-to-use or operational skills do not promote a mind set or application of knowledge to make changes, improvements or modifications to existing systems themselves, but merely accept that the way they work is fixed and unchangeable. Operational skills merely allow tasks to be executed according to the pre-existing task structure through algorithms and code designed by a relatively small number of skilled software engineers within firms. These systems lock-out the possibility of further innovation or generative potential, what Zittrain refers to as potential generativity as ‘sterile appliances tethered to a network of control’ [Zittrain, 2008]. Measures put in place to fully control the user experience and maintain quality control, but also and more fervently to protect inter-firm intellectual property and appropriation of rents from within a competitive landscape; not for protecting against un-sanctioned, valued consumer acts of hacking that further-extend an artefacts’ repertoire of task execution possibilities.

One of the founding members of Raspberry Pi recently surmised what he hoped the device would achieve: ‘getting kids to engage creatively with computers: doing interesting things... it doesn’t have to be programming: it can be art [or] design, using computers in a creative way’ [Joyce, 2012]. This also begins to surmise fundamental attributes at the core of the hacker ethics. It mirrors the activities undertaken by firms in the search for new innovation (both radical and incremental) within R&D labs; the main difference being creatively exploring yet-to-be-realised technology configurations to be used in creating new products and services, rather than modifications to existing ones by its users.

Many of today’s digital devices (whether tethered to a network of control or open to modification) have a predefined set of operable functions and tasks inherent in its architecture and limited by its design. Hackers in this sense provide a means and a method to access and contribute to the generative or innovative potential held within a given technology. Whether closed by measures put in place by manufacturers or freely accessible in open systems, hackers will find ways in which to unlock the potential generativity within a technology. There are no true closed systems in the mind of the hacker, only temporary, inconvenient obstacles to overcome (firmware, software and hardware locks, encryption, copy protection, digital rights management and many others) and re- enable open or modifiable devices in the pursuit of executing further tasks with a technology whether deemed legal or otherwise.

The RasPi is an interesting market proposition, built with extremely low barriers to entry due to the £22 price tag and designed with a sole reliance on leveraging hacker communities to enable its future adoption and success. It was initially targeted at Computer Hobbyist and Enthusiast Programmers to build and develop an Open Source software base before educational institutions could begin adopting them in classrooms with a recently pre-built and rich software base.[2] The product launch strategy was intended to leverage hacker ethics, seen as passionate and playful explorers of technology, by selling ten thousand initial units to end users and hacker-innovators ahead of mainstream markets.

The computer is entirely open by design to easily permit the seeking of ways in which to execute new tasks outside those thought possible by the original architects and designers, representing an altogether different strategy to those employed by multinational technology incumbents. The RasPi foundation is trying to actually encourage and generate a culture of hackers, who inquisitively seek to control technology, not be controlled by it.

To innovate on the RasPi, hackers do not need to circumvent barriers, copy protection, encryption standards, locked hardware or bootloaders in order to explore generative and innovative potential. If the Raspberry Pi was designed and manufactured at the same price, with a range of locked-out functionality and features in order to protect various intellectual property rights, hackers would soon find a variety of ways to jailbreak the device, enable further exploration of its generative potential, whether through software or hardware ‘mods’ (as has repeatedly been seen with the proprietary and closed devices using Apple’s iOS).

Users are free to simply operate the device but the main intention is for users to modify it in any way they see fit. Generations of mainstream users have grown used to simply operating desktop PC’s, games consoles, mobile phones and tablets as complex and fragile mystical black boxes with intentional safety locks to prevent untrained users from modifying it via complex and incomprehensible layers of sophisticated code.

Critics of RasPi have commented that children in particular are simply not interested in modifying and creating code, claiming they see devices as simple and dull black boxes akin to washing machines or vacuum cleaners, interested only in the tasks they can achieve, not in how tasks are achieved or modifying the way in which tasks are executed [Rockman, 2012].

This may be true in many cases, but the RasPi represents an experimental, open challenge to hacker and student communities alike both young and old and it remains to be seen exactly how much generativity can be unleashed and its long term influence on future generations of innovators, hackers and entrepreneurs World wide.

Case Study: Black Mesa Source Game Mod

In September 2012 forty computer game mod hacker developers released the eagerly awaited, updated and expanded re-make of a game called Black Mesa Source. It was based on the critically acclaimed first-person-shooter, Half-Life, originally released in 1998 by developers, Valve. After eight years of development the game mod was released for free to the community, designed and built using Valve’s own software develop kit (SDK), to enable hacker-fans to create their own in-game content and mods that could run on the Source engine. Such mods were encouraged by the firm due to the complimentary potential to existing products and further expansion made possible using the existing suite of internally developed games that would in turn generate future rents for the firm.

The project is an example of end-user hackers using toolkits to enable the creation of new and complimentary value from outside organisational boundaries [Piller, 2004] [Piller and Walcher, 2006]. In this instance the purpose of the project was not commercially motivated as the game was released for free. Instead, the motivation came from the technical failings and sub-optimal modular optimisations of an internally developed innovation or port of the original game using the first generation engine to the more advanced second-generation engine named Source. Valve had simply taken the modular design of the older game and ported it to the newer engine without taking full advantage of more advanced rendering technologies made available to the developers in the upgraded engine.[3] At the time, Valve were in the process of developing several of its other leading edge mods using the Source engine and had subsequently chosen to deploy its internal resources in developing these latest generation innovations, instead of allocating them in resurrecting older generation projects to latest technological standards. This typical draw to the most valuable commercial growth driven strategy left an open gap for hacker innovators to fill who felt that Valve had not fully optimised design modules to their most innovative potential and were significantly passionate, skilled and motivated enough to set about deploying resources of their own by entering into software development for themselves.

Footnotes

- Jump up ↑ Google's Eric Schmidt criticises education in the UK (http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-14683133), August 2011).

- Jump up ↑ Raspberry Pi is based on a Broadcom BCM2835 system on a chip (SoC) using ARM architecture chips (commonly used in smartphones) in order to keep per unit prices as low as possible.

- Jump up ↑ New game engine features that were available included vertex and pixel shaders for more realistic water effects; a more advanced Havok physics engine; dynamic light maps; vertex maps, rag dolls and new shadowmap system all using high resolution texture maps.

References

- [Joyce, 2012] ^ 1 2 Joyce, J. (2012). "Raspberry Pi computer: Can it get kids into code?". Retrieved April 3, 2012, from http://m.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-17192823.

- [Zittrain, 2008] ^ Zittrain, J. (2008). The Future of the Internet And How to Stop It New Haven & London, Yale University Press.

- [Rockman, 2012] ^ Rockman, S. (2012). "Is raspberry pi a mid-life crisis?". Retrieved April 15, 2012, from http://www.zdnet.co.uk/blogs/fuss-free-phones-simon-rockman-10024919/is-raspberry-pi-a-mid-life-crisis-10025449/.

- [Piller, 2004] ^ Piller, F. N., Franke (2004). "Value Creation by Toolkits for User Innovation and Design - The Case of the Watch Market." Journal of Product Innovation Management 21(6): 401-415.

- [Piller and Walcher, 2006] ^ Piller, F. T. and D. Walcher (2006). "Toolkits for idea competitions: a novel method to integrate users in new product development." R & D Management 36(3): 307-318.

- [Sharma, 2012] Sharma, A. (2012). "Stuxnet - First Cyber Weapon of the World." Retrieved April 11, 2012, from http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/stuxnet-first-cyber- weapon-world.

- [Nappenberger, 2012] Nappenberger, B. (2012). We Are Legion: The Story of the Hacktivists.

- [IDEO, 2012] IDEO (2012). "IDEO Labs Bay Area Hack Nights." Retrieved Feb, 2012, from http://labs.ideo.com/2012/03/13/bay-area-hack-night/