Hacker Generations and Evolution

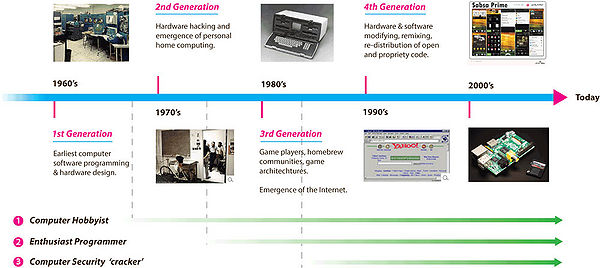

Although the extant typology of hacker activities along the illegal-to-legal dimension is useful in delineating differing types in terms of destructivity, creativity, piracy and theft, remixing of value etc., it does not take into account the evolution of different hacker types over time since their initial emergence. The typology assumes all hackers are constituent of the same generation, which is clearly not the case, given the incremental emergence of hacker generations since the 1960’s (see below).

Figure 1. Emergence of hacker types and generations.

Viewed in this way in temporal form, the Computer Security Crackers are a relatively new phenomenon; an inevitable result by those seeking to exploit and illegally profit from new emergent and openly available technologies (distributed home computing, micro-chips, networks and Internet communication technologies).

Computer Hobbyists and Enthusiast Programmers emerged long before Computer Security Crackers (despite the current focus of meaning in popular culture) and in some instances created entire industries as in the personal home computing sector.

Hackers were in fact first defined in 1984 in a book called Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution, described as having evolved through several generations. An extension of this is offered below.

Contents

1st Generation Hackers (1960’s/70’s)

- Hackers involved in the earliest computer programming techniques development for technology exploration.

2nd Generation Hackers (mid 1970’s to mid 1980’s)

- Hackers in computer hardware production during the advent of Personal Computer by modifying and creating new hardware configurations (Apple, Microsoft: Jobs, Wozniak, Allen, Gates et al.).

3rd Generation Hackers (1980’s to mid 1990’s)

- Hacker-game players devoting leisure time to writing scripts and programmes for game architectures amidst the emergence of Open Source software development [Jeppessen, 2003].

4th Generation Hackers (late 1990’s to today)

- Hackers freely modifying, remixing, reconfiguring and re- distributing open and proprietary knowledge extracted from creative IP from consumer artefacts, technology, products and services facilitated by the use of information and communication technologies (ICT’s).

There is a significant need to understand the true meaning of hacking, not from a sensationalist media perspective but from its origins to uncover its motivation, goals and aims; and to find exactly what role hacking plays in today’s digitally networked society. Media coverage of hacking does nothing to promote scholarly attention to the understanding of the wider role hacking plays, and merely demotes it to illegal deviant activities involving crime, dark sub-cultures with gang mentalities. In some contexts along the illegal-to-legal dimension, these perceptions are entirely valid, but they do not hold for all types of hacking activity that can represent generativity, creativity and problem solving solutions. Only by broadening our understanding of hacking can we begin to see other forms of hacking that are not simply negative and destructive but are creative sources of potential innovation by hacker-innovators and end users alike that can be a significantly beneficial source for organisations seeking to create better experiences, products and services for their consumers.

Re-framing the extant hacker typology

Common to all forms hacking activity along the illegal-to-legal dimension, are set of cultural beliefs and values that can shed light on motivations for the initiation of a hack in the first place. The table below shows a summary of the three main hacker activity types and the degree to which such acts may be deemed illegal by institutions or organisations claiming private intellectual property ownership over artefacts.

Figure 2. Typology of hacker classes along legal to illegal/closed to open dimensions.

As discussed so far, illegal and negatively perceived activities (in a non-market value generation sense) form only part of overall hacking landscape, despite being those that predominate in the popular media and resulting cultural consciousness. Other forms of hacking clearly do exist, albeit perhaps to lesser degrees of illegality in combination with some market value generating potential.

Analysing hacker activities along a negative (destructive-illegal) to positive (generative-legal) dimension allows us to break away from the stereotypical, popular cultural understanding of hacking by expanding our moral and ethical boundaries outside the stereotypical notions of deviant, criminal acts. Once this is understood, other, possibly illegal but generative and perhaps useful forms of hacking can be discussed and explored. This is highly important as firms should not simply, automatically and instinctively condone, disregard, legislate against and prosecute forms of hacking by users as a threat to firm interests, at least not in all hacking cases. Instead, a deeper understanding is needed to seek-out potential commercial uses for such activities, by engaging with or even encouraging hacker activities in order to gain knowledge that would not otherwise be generated by standard internal research and development processes. Firms that can leverage this typically unrealised source of innovation will gain a vital source of complimentary knowledge. This could be used to help future product design and development generations, inform upon industry and product class design trajectories, as well as help build open modularity into complex systems and promote social innovation development where desired. Much of this could help firms gain additional unrealised competitive advantage over those firms with a typically closed market strategy and sole internal R&D by leveraging activities within forms of hacker innovation.

If considered in this wider sense, hacking can be framed as a communal pool of expert knowledge and skills applied with passionate-inquisitiveness to an existing technological artefact as a source of innovation or value generation, whether for the general market or personal consumption.[1] Outcomes as to the usefulness of overall hacker innovation activities are dependent upon a number of institutional factors, political motivations, firm interests, desires, morals and ethics.

In a broader contextual framing, destructive criminal hacking acts form only a small proportion of the overall activities undertaken in the unconstructive, non- generative sense, particularly for innovating organisations. There is however an academically under-researched area of innovation (between script kiddies and end-user innovators) that lies beyond the market usefulness boundary, known as the hacker-innovator class (see diagram below).

Figure 3. The illegal-to-legal dimension: degrees of legality and openness with potential market usefulness through hacker activities.

The market usefulness boundary generally delineates the point at which a potential source of innovation begins to emerge and could prove useful to firms engaged in the development management of their product innovation classes. Exploiting an innovation source such as this should have the potential enable the link between producers and consumers to be tighter by improving the performance, quality, features and other consumer value metrics, used for reducing uncertainty in the innovation process of future product class generations.

Non-generative potential acts of cracking fall under the same definition as illegal cracker activities and are classed beyond the generalised market usefulness boundary (in diagram above). These do not typically offer potential sources of innovation or design trajectory information for firms in terms of generativity due to the closed, secretive and semi-mysterious nature of activities and therefore fall outside the scope of discussion in this thesis.

Also of note are the underlying hacker ethics with regard to the degree of information openness. More illegal hacker activities tend to operate in closed, secretive groups, intentionally working under institutional radars, governmental infiltration and tracking measures due to the highly prosecutable nature of activities undertaken.29 End-user or external innovation on the other hand tends to operate in more open environments (similar to the scientific and academic communities for communal knowledge generation), mid-way along the illegal to legal dimension where sharing knowledge and information is more commonly found. Toward the legal end, information is once again held proprietary or closed where innovation models are in place and designed to allow firms survival and growth by maintaining competitive advantage from the appropriation of rents from proprietary intellectual property regimes and supporting international legal frameworks.

In Figure 3 (above) the relationship between (a) illegal, closed (b) semi-illegal, open and (c) legal, closed is interesting in the context of innovation studies.[2] If highly illegal information and data theft (Computer Security Crackers) at (a) is disregarded from further discussion for the sole reason that it tends not to generate market tradable value as a general rule, what remains is a dichotomy between open and closed forms of market value generation or potential innovation sources.

Activities that do not have inherent potential usefulness to firms in this way are resigned to the Computer Security Cracker group alone. The usefulness landscape then appears more concise based solely on forms of generativity as follows:

Figure 4. The potential generative hacker landscape: open (illegal) to closed (legal) acts.

Figure 4 outlines the more concise hacker activity landscape and forms a wider perspective view of the field of interest to researchers and firms alike in isolating and leveraging any generative external innovation sources that may create market value or competitive advantage for industries. A significant amount of academic research has been dedicated to end users and lead user innovation [von Hippel, 1986] [Jeppesen and Molin, 2003] [von Hippel, 2005] [Baldwin, Hienerth et al., 2006] [Piller and Walcher, 2006] [Prugl and Schreier, 2006] [Schreier, Oberhauser et al., 2007] [Baldwin, 2010] [Bogers, Afuah et al., 2010] [Gassmann, Enkel et al., 2010] and Open Source [Lakhani and von Hippel, 2001] [Baldwin, 2003] [Hertel, Niender et al., 2003] [Lerner and Jean, 2003] [von Hippel, 2003] [Weber, 2004] [Ven and Verelst, 2008], but less focus has been made specifically within the study of hacker innovation itself [Hannemyr, 1999] [Lin, 2002] [Lakhani, 2003] [Mollick, 2004] [Flowers, 2006] [Berthon, 2007] [Flowers, 2007] [Lin, 2007] [Schulz, 2008] [Schulze and Hoegl, 2008] [von Hippel, 2008] [Sarma, 2009] [Robertson, 2010]. Conceptualised in this way, hacker innovation and hacker ethics form and underpin nearly all-external innovation activities by end users and consumers in some form. Extant research in the area has implicitly acknowledged hacking in various guises as a driver in external innovation phenomena, but not explicitly correlated hacker ethics and motivations in the broader context of perhaps illegal, private property infringement instances, irrespective of the potential to provide vital sources of innovation to firms. This is most likely due to the morally grey area in which these activities occur to varying degrees of illegality; resulting difficulties in sourcing funding from research councils and academic institutions that may be seen to advocate and cheerlead for fundamentally illegal activities.

Footnotes

- ↑ Instead of simply stealing data or breaking into computer systems in the Computer Security Cracker sense.

- ↑ 30 These relationships are based on a rather simplistic assumption that hacker activities are unconstructive and negative and this may not always be the case. Some hacker activities that may be deemed illegal and negative to firms may actually have some wider societal benefit, as was the case with the Anonymous group uncovering and hacking into a child pornography group and publishing names of those users subscribed, forcing the closure and prosecution of those sharing highly illegal and morally controversial digital media between peers.

References

- [Jeppessen, 2003] ^ Jeppessen, L. B. M., M. (2003). "Consumers as Co-Developers: Learning and Innovation Outside the Firm." Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 15(3).

- [von Hippel, 1986] ^ von Hippel, E. (1986). "Lead Users: A Source of Novel Product Concepts." Management Science 32(7): 791-805.

- [Jeppessen and Molin, 2003] Jeppesen, L. B. and M. J. Molin (2003). "Consumers as co-developers: Learning and innovation outside the firm." Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 15(3): 363-383.

- [von Hippel, 2005] ^ von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press.

- [Baldwin, Hienerth et al., 2006] ^ Baldwin, C., C. Hienerth, et al. (2006). "How user innovations become commercial products: A theoretical investigation and case study." Research Policy 35(9): 1291-1313.

- [Piller and Walcher, 2006] ^ Piller, F. T. and D. Walcher (2006). "Toolkits for idea competitions: a novel method to integrate users in new product development." R & D Management 36(3): 307-318.

- [Prugl and Schreier, 2006] ^ Prugl, R. and M. Schreier (2006). "Learning from leading-edge customers at The Sims: opening up the innovation process using toolkits." R & D Management 36(3): 237-250.

- [Schreier, Oberhauser et al., 2007] ^ Schreier, M., S. Oberhauser, et al. (2007). "Lead users and the adoption and diffusion of new products: Insights from two extreme sports communities." Marketing Letters 18(1-2): 15-30.

- [Baldwin, 2010] ^ Baldwin, C. v. H., E. (2010). "Modelling a Paradigm Shift: From Producer to User and Open Collaborative Innovation." MIT Sloan School of Management Working Paper No.4764-09.

- [Bogers, Afuah et al., 2010] ^ Bogers, M., A. Afuah, et al. (2010). "Users as Innovators: A Review, Critique, and Future Research Directions." Journal of Management 36(4): 857-875.

- [Gassmann, Enkel et al., 2010] ^ Gassmann, O., E. Enkel, et al. (2010). "The future of open innovation." R & D Management 40(3): 213-221.

- [Lakhani and von Hippel, 2001] ^ Lakhani, K. and E. von Hippel (2001). "How opensource software works: 'free' user-to-user assistance." MIT Sloan Management Review 32(6): 923-943.

- [Baldwin, 2003] ^ Baldwin, C. C., B. (2003). "The architecture of cooperation - how code architecture mitigates free riding in the open source development model." Mit Sloan Management Review.

- [Hertel, Niender et al., 2003] ^ Hertel, G., S. Niender, et al. (2003). "Motivation of software developers in OpenSource projects: an Internet-based survey of contributors to the Linux kernel." Research Policy 32(7): 1159-1177.

- [Lerner and Jean, 2003] ^ Lerner, J. and T. Jean (2003). "Some Simple Economics of Open Source." The Journal of Industrial Economics 50(2): 197-234.

- [von Hippel, 2003] ^ von Hippel, E. v. K., G. (2003). "Open Source Software and the Private-Collective Innovation Model - Issues for Organization Science." Organization Science 14(2): 209-223.

- [Weber, 2004] ^ Weber, S. (2004). The Success of Open Source, Cambridge University Press.

- [Ven and Verelst, 2008] ^ Ven, K. and J. Verelst (2008). "The impact of ideology on the organizational adoption of open source software." Journal of Database Management 19(2): 58- 72.

- [Hannemyr, 1999] ^ Hannemyr, G. (1999). "Technology and Pleasure: Hacking Considered Constructive." from http://hannemyr.com/en/oks97.php.

- [Lin, 2002] ^ Lin, Y. (2002). Pan-hacker culture and unconventional software innovation: exploring the socio-economic dimensions of Linux. Linux Tag 2002. Karlsruhe, Germancy.

- [Lakhani, 2003] ^ Lakhani, K. W., R. (2003). Why Hackers Do What They Do: Understanding Motivation and Effort in Free/Open Source Software Projects. Perspectives on Free and Open Source Software. B. F. Joseph Feller, Scott A. Hissam, Karim Lakhani. Cambridge Massachusetts. London, England, MIT Press.

- [Mollick, 2004] ^ Mollick, E. (2004). Innovations From The Underground: Towards a Theory of Parasitic Innovation. SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT Harvard University. Master of Science.

- [Flowers, 2007] ^ Flowers, S. (2007). From Outlaws to Trusted Partners: Challenges in mobilising User-Centric Innovation in R&D projects. Centre for Research in Innovation Management (CENTRIM), University of Brighton. Brighton, University of Brighton (CENTRIM).

- [Flowers, 2006] ^ Flowers, S. (2006). KNOWLEDGE, INNOVATION AND COMPETITIVENESS: DYNAMICS OF FIRMS, NETWORKS, REGIONS AND INSTITUTIONS. DRUID Summer Conference 2006. Denmark.

- [Berthon, 2007] ^ Berthon, P. P., L. McCarthy, I. Kates, S. (2007). "When customers get clever: Managerial approaches to dealing with creative consumers." Business Horizons 50: 39-47.

- [Lin, 2007] ^ Lin, Y. (2007). Hacker Culture and the FLOSS Innovation Handbook on Research in Open Source Software: Technological, Economic and Social Perspectives. K. S. St.Amant, Brian. Idea Group.

- [Schulz, 2008] ^ Schulz, C. W., S. (2008). Outlaw Community Innovations. Munich School of Management, University of Munich.

- [Schulze and Hoegl, 2008] ^ Schulze, A. and M. Hoegl (2008). "Organizational knowledge creation and the generation of new product ideas: A behavioral approach." Research Policy 37(10): 1742-1750.

- [von Hippel, 2008] ^ von Hippel, E. P., J. (2008). User Innovation and Hacking. Pervasive Computing, IEEE C5. 8: 66.

- [Sarma, 2009] ^ Sarma, M. L.-F., J. Clark, E. (2009). VIRTUAL INNOVATION WITHIN A HACKER COMMUNITY AN EMPIRICAL STUDY OF OPEN SOURCE SOFTWARE DEVELOPMENT. Duid Summer Conference 2009. Copenhagen Business School.

- [Robertson, 2010] ^ Robertson, D. (2010). Hacker Spaces, Georgia Institute of Technology.